Sunday's New York Times did a story on "the next great adventure-travel destination": Kabul. "Even though much of Afghanistan remains dangerous, tourists are beginning to trickle back in, some lured by the thrill of the unknown, others by the pleasures offered by such new tourist spots as the Kabul Serena, an elegant $36.5-million hotel that claims a 'five-star ambiance' in the heart of the city. As many as 5,000 Western tourists visited Kabul last year, Jonathan Bean told me, most of them affluent Europeans and Americans who have traveled to '30 or 40' countries, including developing ones. 'Most our clients are experienced travelers,' Jonathan said. 'They’ve trekked in Nepal, gone on safari in East Africa. Some have returned after coming here in the 1960s and 1970s. They see Afghanistan as the next great adventure-travel destination.'"

I'd love to go back to Afghanistan some time. I'm sure I won't; too dangerous. I first went close to 40 years ago, right out of college. It was a major way station on the "hippie trail" from Istanbul to New Delhi. I was driving a 1969 red VW camper I had bought in Weisbaden and Afghanistan was far more than just a way station to me. Driving across Asia, by the time you get to Afghanistan you know for sure you're not in Kansas anymore, nor in Europe. It was the most foreign place I had ever been. So different from anything I had ever experienced. It felt as much as like traveling in time (backwards) as traveling in space.

There never were any railroads to Afghanistan so the only way to get there before the late 50s was as part of an army. Then the U.S. and the Soviet Union built a road around the country. The U.S. built one from Herat on the Iranian border south and east to Khandahar and up to Kabul and the Soviets built one from Kabul up to Mazar-i-Sharif and then on to Herat. Basically it was the only paved road in the country and now, from what I understand, it is mostly unpaved... destroyed by decades of war and civil neglect.

I drove my van from Meshed in Iran to Herat. It was love at first sight-- mostly with the cheap, powerful hash and the Afghan people who were all stoned all the time. It always boggles my mind now how the mainstream media reports on the wars in Afghanistan but never mentions that every Afghan is stoned-- really stoned-- all the time. It probably has a significant effect on their way of fighting. Herat was like this magical medieval city, completely outside my realm of experience. And the next stop, Khandahar was even more bizarre, most strange, more mysterious and foreign. I felt like I was in Biblical times. Before going up to Kabul I visited some college friends who were in the Peace Corps, stationed in Ghazni. So primitive! But wonderful, warm, friendly generous people. They shared whatever they had.

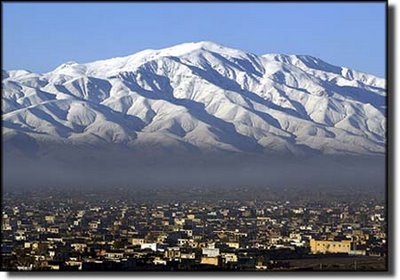

I spent a lot of time in Kabul. Two Canadians who I had driven across Asia settled in to the one western hotel in the city, the brand new Intercontinental. It was a luxury high-rise in the middle of a basically mud city that looked like it would take a week of strong rain to just wash away. I'll never forget the Kabul River, more like a series of trickles and puddles in the middle of town. I recall standing near the royal palace, one of the few substantial buildings in the city, and looking down at the river. Men were on the bank brushing their teeth, washing their clothes, bathing, going to the bathroom, washing a donkey...

The other new thing in this ancient city that year was the Kabul Zoo. It was a wonder for the Afs... a little rinky-dink for the foreigners. But everyone was stoned and everyone was enjoying everything. Except the Kabul Runs. No one enjoys that-- much worse than Montezuma's Revenge. Up and down Chicken Street there were European and Australian hippies staying in cheap flop houses and sick with the Kabul Runs. The music was great and the hash was the best and the food was fine and everything was so cheap. And you'd sit around and talk with people who had come back from Bamyan and the Hindu Kush and Mazar and the Khyber Pass and figure out where you wanted to go next. The king was still in charge and the Russians hadn't invaded yet. I remember seeing some mullahs, straight from the countryside, outraged that 2 young women got out of a car unaccompanied-- albeit covered head to toe (with just a little grill for the eyes) in a chadris (what they call a burqa everywhere else). They spat all over them. The scene has stuck with me for all these decades.

UPDATE: NOT SO FAST

I slept in my van the whole time I was in Kabul in 1969 and in 1972. But friends of mine stayed at the Intercontinental, the only western style hotel in the

A thunderous explosion struck a 2-year-old Kabul luxury hotel frequented by foreigners on Monday, and the Taliban took responsibility, calling it a coordinated assault by four men armed with guns and suicide belts.

The Interior Ministry said at least six people were killed and at least six were wounded in the explosion at the Serena Hotel, including two foreign officials it did not identify... The Associated Press quoted an American who was exercising in the hotel gym as saying that she heard gunfire after the explosion, and saw a body and pools of blood in the lobby area and bullet marks in the gym area. She asked not to be identified for her safety. Ambulances and American troops in Humvees rushed to the hotel after attack, the A.P. reported.

Things are obviously deteriorating? You think so?

One Year On And Nothing's Any Better

This is a post from a western woman, a filmmaker, working in Kabul. It very much captures the Kabul I recall, only it's much worse. Is it a place you'd be interested in visiting? I recommend reading the whole thing at the link. Here are some excerpts:

Going out to dinner is always an interesting experience. Fully covered from head to toe and always paranoid about forgetting a headscarf (or having it slip off your head in the car) generally make the experience more worrisome than enjoyable. Add checkpoints and Afghan police to the mix, along with bone-shaking car rides (no paved roads) and you get the picture.

In New York and New Delhi, I savored going out; dressing up, wearing new jewelry, getting to try new restaurants before meeting friends at a local bar for a drink. I don’t miss these things in Afghanistan – I came here knowing full well that my social life would change drastically (after all, I could’ve just stayed in NYC or Delhi if that’s all I wanted). But what I didn’t expect to change was the very vocabulary of my behavior.

In other cities, I have never thought twice about the fact that I couldn’t enter places without ensuring that I wouldn’t mistakenly brush past a man, that I had to give all men the right of way, and that I wasn’t allowed to speak to strangers or look at other men in the face. In Kabul, I do.

My first weeks here were the most painful-- having to unlearn everything I had picked up in rambunctious, loud Delhi. In Kabul, I felt like as if I was a captive-- wrapped around the head with a scarf that acted as a leash that instructed me to behave in a certain way. My first week was a string of commands from my male, Afghan co-workers and crew, who for my sake taught me how to behave on the streets – “don’t laugh too loud,” “keep your hands hidden,” “don’t say things too loud,” “try and keep your chin down,” “stop walking like you own the street!” And the ever familiar, “wear your headscarf tighter, Anita-jaan, it is falling off!”

...Like all local women in the neighborhood, I can’t leave the house alone. People outside of Afghanistan are shocked to hear this – “but the Taliban have left, no?” Yes indeed, but the Taliban did not make these rules. Many of these rules were actually enforced and created during the time before the Taliban by warlords who, bloated with arms and cash from Pakistan and the US (in order to defeat the Russians), fractured the country.

After the Taliban were defeated, those same warlords were brought back into power by the US. The Karzai government resumes must read like a list charges at an international tribunal. The human rights’ violations are endless. And it is thanks to them (and not the Taliban) that I have to live in a capital city shuttered by extreme conservatism.

A male partner must accompany me at all times outside the house. This ranges from the chowkidor to my husband to friends. Sometimes my husband’s translator comes along, humming as he walks ahead expecting me to follow blindly. When I want to stop, I ask the shopkeeper a question-- usually the price of something – making sure I’m extra loud to ensure he has heard me, and will stop humming and hurry over to where I am.

He carries everything after I’m done shopping. Per his instructions, I shouldn’t carry anything since I’m a woman. By month three, I have learned to walk behind him, lift nothing and simply head home as quickly as I can. He is a Pashtun from the south and older than I am.

The same translator is puzzled when my husband asks me what I want for dinner or lunch. He looks at our exchanges quizzically. We look Indian to him, and yet behave so differently from the Indians he sees in the soap operas he and his family watch at home. In that world men and women are often just as conservative as the Afghans, with each gender culturally filling very different roles. The women are meant to be docile, devoted wives, while the female evildoers are the ones who break the mould and wreak havoc among the orderly. My husband and I don’t seem to even understand that we’re different genders. We speak as equals. This is clearly confusing.

In the end, we finish dinner and make our way home through the dark and quiet streets. We paid the bill in dollars. Price-wise it would amount to the same if I had dined out in New York City. “Restaurants for expats charge expat prices,” explained a friend when I first arrived, “make sure you always have enough cash.” On the way home, my housemate reminds me that we are paying for more than just plates of pasta – we pay for the experience of normalcy. Or the closest thing to normal at least. We both agree it wasn’t for the food at any rate. It wouldn’t survive a New Yorker or New Delhi-ite’s expectations of a good meal (for the price we paid). But tastes change once you’re living in Kabul.

The only meals I have coveted here have been home-cooked Afghan vegetarian dishes prepared by a friend’s mother. Seated on their living room floor, with huge slabs of naan to catch the oil and juices dripping from our fingers, I have devoured bowls of red kidney beans steamed with onions and tomatoes and spices with plates of eggplant slices sautéed with tomatoes and topped with a tangy yoghurt sauce.